From THE BOOK OF WERE-WOLVES

by SABINE BARING-GOULD

Smith, Elder & Co., London

1865

English folklore is singularly barren of werewolf stories, the reason being that wolves had been extirpated from England under the Anglo-Saxon kings, and therefore ceased to be objects of dread to the people.

The traditional belief in were-wolfism must, however, have remained long in the popular mind, though at present it has disappeared, for the word occurs in old ballads and romances.

Thus in Kempion–

O was it war-wolf in the wood?

Or was it mermaid in the sea?

Or was it man, or vile woman,

My ain true love, that mis-shaped thee?

There is also the romance of William and the Were-wolf in Hartshorn; (1) but this professes to be a translation from the French:

For he of Frenche this fayre tale ferst dede translate,

In ese of Englysch men in Englysch speche.

[1. HARTSHORN: Ancient Metrical Tales, p. 256. See also “The Witch Cake,” in CRUMEK’S Remains of Nithsdale Song.]

In the popular mind the cat or the hare have taken the place of the wolf for witches’ transformation, and we hear often of the hags attending the devil’s Sabbath in these forms.

In Devonshire they range the moors in the shape of black dogs, and I know a story of two such creatures appearing in an inn and nightly drinking the cider, till the publican shot a silver button over their heads, when they were instantly transformed into two ill-favoured old ladies of his acquaintance. On Heathfield, near Tavistock, the wild huntsman rides by full moon with his “wush hounds;” and a white hare which they pursued was once rescued by a goody returning from market, and discovered to be a transformed young lady.

Gervaise of Tilbury says in his Otia Imperalia–

“Vidimus frequenter in Anglia, per lunationes, homines in lupos mutari, quod hominum genus gerulfos Galli vocant, Angli vero wer-wlf, dicunt: wer enim Anglice virum sonat, wlf, lupum.”

Gervaise may be right in his derivation of the name, and were-wolf may mean man-wolf, though I have elsewhere given a different derivation, and one which I suspect is truer. But Gervaise has grounds for his assertion that wér signifies man; it is so in Anglo-Saxon, vair in Gothic, vir in Latin, verr, in Icelandic, vîra, Zend, wirs, old Prussian, wirs, Lettish, vîra, Sanskrit, bîr, Bengalee.

There have been cases of cannibalism in Scotland, but no bestial transformation is hinted at in connection with them.

Thus Bœthius, in his history of Scotland, tells us of a robber and his daughter who devoured children, and Lindsay of Pitscottie gives a full account.

“About this time (1460) there was ane brigand ta’en with his haill family, who haunted a place in Angus. This mischievous man had ane execrable fashion to take all young men and children he could steal away quietly, or tak’ away without knowledge, and eat them, and the younger they were, esteemed them the mair tender and delicious. For the whilk cause and damnable abuse, he with his wife and bairns were all burnt, except ane young wench of a year old who was saved and brought to Dandee, where she was brought up and fostered; and when she came to a woman’s years, she was condemned and burnt quick for that crime. It is said that when she was coming to the place of execution, there gathered ane huge multitude of people, and specially of women, cursing her that she was so unhappy to commit so damnable deeds. To whom she turned about with an ireful countenance, saying:–‘Wherefore chide ye with me, as if I had committed ane unworthy act? Give me credence and trow me, if ye had experience of eating men and women’s flesh, ye wold think it so delicious that ye wold never forbear it again.’ So, but any sign of repentance, this unhappy traitor died in the sight of the people.”

[1. LINDSAY’S Chronicles of Scotland, 1814, p. 163.]

Wyntoun also has a passage in his metrical chronicle regarding a cannibal who lived shortly before his own time, and he may easily have heard about him from surviving contemporaries. It was about the year 1340, when a large portion of Scotland had been devastated by the arms of Edward III.

About Perth thare was the countrie

Sae waste, that wonder wes to see;For intill well-great space thereby,

Wes nother house left nor herb’ry.

Of deer thare wes then sic foison (profusion),

That they wold near come to the town,

Sae great default was near that stead,

That mony were in hunger dead.

A carle they said was near thereby,

That wold act settis (traps) commonly,

Children and women for to slay,

And swains that he might over-ta;

And ate them all that he get might;

Chwsten Cleek till name behight.

That sa’ry life continued he,

While waste but folk was the countrie.

[1. WYNTOUN’S Chronicle, ii. 236.]

We have only to compare these two cases with those recorded in the last two chapters, and we see at once how the popular mind in Great Britain had lost the idea of connecting change of form with cannibalism. A man guilty of the crimes committed by the Angus brigand, or the carle of Perth, would have been regarded as a were-wolf in France or Germany, and would have been tried for Lycanthropy.

S. Jerome, by the way, brought a sweeping charge against the Scots. He visited Gaul in his youth, about 880, and he writes:–“When I was a young man in Gaul, I may have seen the Attacotti, a British people who live upon human flesh; and when they find herds of pigs, droves of cattle, or flocks of sheep in the woods, they cut off the haunches of the men and the breasts of the women, and these they regard as great dainties;” in other words they prefer the shepherd to his flock.

Gibbon who quotes this passage says on it: “If in the neighbourhood of the commercial and literary town of Glasgow, a race of cannibals has really existed, we may contemplate, in the period of the Scottish history, the opposite extremes of savage and civilized life. Such reflections tend to enlarge the circle of our ideas, and to encourage the pleasing hope that New Zealand may produce in a future age, the Hume of the Southern hemisphere.”

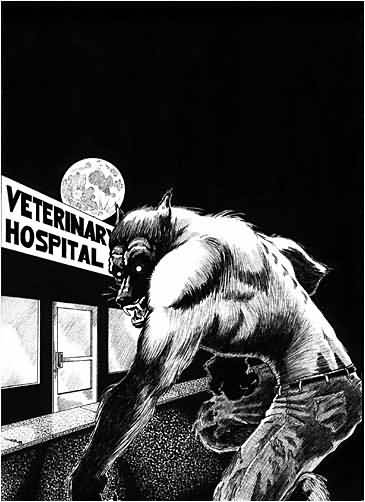

Records of an enormous wolf-like animal in North Wales date back to 1790, when a stagecoach travelling between Denbigh and Wrexham was attacked and overturned by an enormous black beast almost as long as the coach horses.

The terrifying animal tore into one of the horses and killed it, while the other horse broke free from its harness and galloped off into the night.

The attack took place just after dusk, with a full moon on the horizon. The moon that month seemed blood red, probably because of dust in the stratosphere from a recent forest fire in the Hatchmere area.

The locals thought the moon’s colour was a sign that something evil was at large and the superstitious phrase, “bad moon on the rise” was whispered in travellers’ inns across the region. In the winter of 1791, a farmer went into his snow-covered field just seven miles east of Gresford, and he saw enormous tracks that looked like those belonging to an overgrown wolf.

He followed the tracks with a blacksmith for two miles, and they led to a scene of mutilation which made the villagers in the area quake with fear that night.

One snow-covered field was a lake of blood dotted with carcasses of sheep, cattle, and even the farmer’s dog.